This article summarizes several issues that are critical to establishing an ASC. The article focuses on business and planning issues and does not focus on legal and regulatory issues for ASCs. In addition, industry experts offer their advice on some of these areas.

Financial planning issues

1. Financial feasibility; a comprehensive feasibility study. A group of physicians (or physicians and management company or hospital) must first examine their outpatient case numbers to determine whether an ASC will be financially feasible. The formula for this is easy: ASC revenue is equal to the number of procedures the group can perform multiplied by the expected reimbursement for the type of procedures expected to be performed. As a general rule, in a reasonable reimbursement market, a center focusing on higher reimbursement procedures can be profitable with as little as 2,000 procedures per year. With lower reimbursement cases, this number can jump to 3,000-3,500 procedures. Further, in low reimbursement markets, it can be very hard to be profitable in some specialties at almost any case level. Financial prudence dictates that one should only begin a project with a case level that is substantially higher than the threshold or break-even amount.

A pro forma analysis and feasibility study can help you determine if establishing an ASC is possible. You should rely on sound physician data regarding projected case volumes, case mix, scheduling preferences and expected reimbursement rates.

The case volume and reimbursement rate data that are collected are the key assumptions upon which the revenue part of pro formas are built. The greater the accuracy and certainty of these two types of information, the greater the accuracy and reliability of the final pro forma projections. In one center we helped to develop, the viability of the project itself was threatened when one or two of the key assumptions changed, resulting in the prospective loss of several hundred cases per year.

In addition, the physician partners involved in the project should be fully committed from the outset. There are few things that will negatively impact the financial outlook for a new center as much as the departure of a core physician during the later stages of development. Although a project can recover from a minor setback or challenge during the early planning stages, it is more difficult to correct more severe problems that occur later in development.

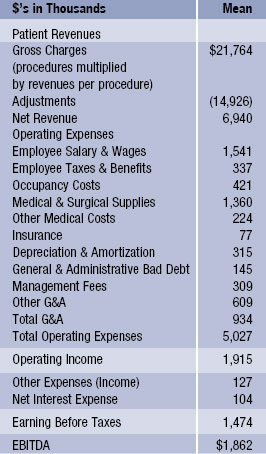

Here is a sample summary pro forma from the VMG Health 2008 Intellimarker:

Case-counting is an essential part of the development process. “Regardless of which specialties you develop the center around, it’s critical to understand the surgical case volume represented by each,” says Catherine Kowalski, executive vice president and chief operating officer of Meridian Surgical Partners. “Determine the universe of surgical case by physician and always calculate the net case transfer to the ASC, factoring in issues that discount volume including insurance contracts, regulatory, politics, convenience, scheduling, surgeon behavior, etc. A good rule of thumb is about 50 percent of the surgical case universe for a conservative analysis.”

Attendance at planning meetings is another crucial part of the development process. “If after two meetings to investigate and develop a project your key physician members’ attendance of remains strong, then it is time to get excited,” says William Southwick, CEO of HealthMark Partners. “Every surgeon likes the concept of developing a center; it is the core group that remains after two initial meetings that tells you whether the excitement is real or not.”

2. Reimbursement by market differs significantly; out-of-network concerns. Throughout the country, centers have had difficulty contracting with certain insurance companies. Therefore, in assessing case volumes, it is important discount the number of cases, to a certain extent, in order to reflect the fact that certain insurance plans may not contract with the ASC. Moreover, certain insurance plans and geographic regions reimburse at levels below national standards. Therefore, the center may not be able to provide services to these patients covered by such plans or in such regions. A mediocre ASC located in an area with strong third-party reimbursement may do better than a great ASC in a bad reimbursement market. There is almost no way to fix a center that is built in a market with poor reimbursement from third-party payors.

In the planning stage, the center should attempt to discuss contracting with payors and obtain a real sense of whether contracts will be available and at what price. Payors have increasing power in many markets and are becoming harder to work with on an out-of-network basis. Payors and state regulatory agencies are increasingly scrutinizing out-of-network reimbursement strategies. In recent months, more insurers are attempting to recoup amounts they have paid on an out-ofnetwork basis. Similarly, state agencies have been more aggressively policing this area. In one recent case in New York, state auditors alleged that several surgery centers improperly waived patients’ out-of-pocket payments in connection with the care they received at the centers. In all, the state alleged that about $8 million was overpaid by the state employee insurance plan, the Empire Plan, and United HealthCare, the state’s insurance administrator.

I. Naya Kehayes, MPH, managing principal for Eveia Health Consulting and Management, warns that insurance companies are taking more aggressive approaches to target out-of-network ASCs and encourage in-network participation.

“They are actively pursuing surgeons who practice in non-contracted ASCs and are sending notices to surgeons who use non-contracted ASCs that indicate they are in violation of their professional contracts by directing patients to a non-participating facility,” she says. “Some payors are demanding from surgeons copies of the ASCs’

out-of-network billing practices, policies and procedures. They are threatening to terminate their professional contracts as a result of taking patients to an out-of-network facility.”

In its 2008 annual report on ASCs (dated Feb. 4, 2008), the Deutsch Bank reports that for ASCs, “out-of-network situations typically result in greater overall costs to the system because both the patient and the third-party payor have higher outlays.” The report also notes that, in the long-term, “any ASC that builds its business model around unsustainable out-of-network reimbursement levels is bound to fail.”

One of the benefits of a hospital partner is that it is able to jointly negotiate reimbursement rates or to include the center in on the hospital’s own payor agreements. However, this is often legally restricted as it is subject to certain antitrust rules and regulations that require the hospital to have a sufficient amount of control over the venture on whose behalf it is negotiating. In many situations, the hospital will be unable to force the payors to negotiate on a joint basis. To further complicate matters, some hospitals fear that by seeking to negotiate the ASC’s rates with a particular payor, they will be exposing themselves to renegotiation of their current hospital outpatient department rates.

As out-of-network practices continue to raise concerns, and there is increasing pressure due to the economic environment for providers to be contracted with payors in order to reduce out-of-pocket responsibility to the patient, Ms. Kehayes advises ASCs to develop an in-network strategy.

“A new ASC should evaluate the contracts that their physician-users have in place at their practices and determine the most critical payors,” she says. “It is important that the ASC align its contracts with the surgeons that will be using the center. Products offered by the insurance company should also be evaluated. Often, payors sell HMO as well as PPO products or they have products that are very restrictive with respect to out-of-network benefits. Therefore, if there are product limitations to out-of-network access, these payors are typically more important to get in place soon after an ASC opens.”

Ms. Kehayes suggests that ASCs start making inquires to payors at least six months prior to the opening of an ASC in order to evaluate access to contracts and to speed up the negotiation process. “The initial contracts an ASC secures with a payor are the baseline for the future of all contracts as well as the relationship with the payor,” she says. “The initial contracts present the most opportunity for negotiation especially if the surgeons working at the ASC are moving volume from a more costly environment, the hospital, and to the ASC setting.”

She also warns ASCs against signing contracts just to boost volume as it actually reduces the power of the ASC to renegotiate its contract. Once the ASC signs an initial contract to attain access to volume, and surgery is performed at a contract rate that is below the cost of providing the surgical service, it demonstrates to the payor that the ASC can afford to perform the case for that rate. In reality, the ASC is often subsidizing the insurance company by paying to perform surgery on their members because the contract rates are below cost. The payor is unlikely to make significant changes to rates after the initial contract has been signed and there is a contractual term in place, which can range from 1-3 years.

Some ASCs may find it more advantageous to provide services as an out-ofnetwork provider, when out-of-network benefits are available, for a period of time when the center first opens and while the center is in active negotiations with a payor, according to Ms. Kehayes.

“This helps to demonstrate the cost-savings opportunity to the payor and its members of contracting with the ASC,” she says. “The payor will have claims data showing their opportunity to reduce cost by moving the ASC in-network. In addition, if a center does not provide any services to a particular payor out-of-network while in the contract negotiation process, it is often devalued and it lowers the ASC’s importance on the payor’s contracting priority list. This can prolong the already lengthy contracting process.”

Hiring a third-party contracting consultant is another alternative to consider. A consultant can provide insight and advice with respect to the planning stages of reimbursement contracts. In addition, these consultants ultimately can be used to negotiate the contracts on behalf of the center. Some management company partners employ their own in-house contract negotiators whereas others outsource this function.

3. Capital requirements. The typical development of a standalone ASC with tenant improvements costs approximately $220-$250 or more per square foot to become operational. Additionally, money is needed for equipment. Of the total budget amount, a substantial portion can be provided through debt financing without guarantees; however, a certain portion of the debt may require personal guarantees (such as tenant improvements, working capital, etc.). Moreover, a substantial cash capital contribution is usually required in an ASC venture. Typically, anywhere from $500,000-$1.5 million is required as an equity cash contribution in total by the owners.

An ASC will typically initially issue 100 ownership units to members based on the amount of capital that each member contributes. For example, if each unit costs $10,000 and a member owns 15 units, he or she contributes $150,000. The amount of capital required depends on the size of the project, the amount of debt to be secured and whether the ASC will be a “tenant” or own and develop the real estate. The equity plus the debt borrowed from lenders equals the total amount of money needed to develop the project. If a singlespecialty ASC, such as an endoscopy ASC, leases the space in which it operates, total initial equity capital contributions are often around $400,000- $800,000; however, the members may be able to contribute less money upfront if a more substantial working capital line of credit is obtained. For a multi-specialty ASC that leases space rather than owns the building, initial equity capital contributions are often between $700,000-$1.2 million. One option, even when all of the investors want to invest in both the surgery center and the real estate, is to hold the ownership of the real estate and the ownership of the surgery center in separate entities. This allows for additional investors to own a portion of the real estate holding company, thus making it less expensive for the investors in the surgery center entity. By separating the real estate from the surgery center entity, investors can choose where they would like to invest: in the real estate, the surgery center or both. However, there are significant benefits to fully congruent ownership.

The operating agreement sets forth the dates on which the capital must be contributed. Typically, all or a significant portion is due at signing. In some situations, part of the capital is due at a later date, such as upon receipt of a certificate of need or at six months after the initial signing. Additional capital contributions may be required upon the vote of the board of managers and often a vote of the holders of a certain percentage of the units. The group will need to assess the total equity to be contributed.

Working with experienced lenders will facilitate the financing of an ASC. It can be tempting to work with a friend or a local bank, but this could be a mistake. Often with ASCs, time is of the essence and problems occur which are better handled by an experienced lender than by a friend. For the best result, look for a lender with specific ASC financing experience.

The current state of the economy is something that should be considered heavily when determining financing for your new ASC. Robert Westergard, CPA, CFO of Ambulatory Surgical Centers of America, says that banks are currently looking to see as much as 30-40 percent of the total cost contributed by partners, compared with the 20 percent or lower seen previously.

“In the past, we used our cash only for working capital,” he says. “Some back are asking that we now use some of it in lieu of bank financing for some capital expenditures.”

Mr. Westergard also notes that the banking environment has changed dramatically over the last year. “In the past, banks seemed to be looking for reasons to lend money,” he says. “Now, they’re often looking for reasons not to lend money.” This changed environment also has affected the amount of time it takes to obtain a loan. “We’ve doubled the amount of time we tell our partners to expect obtaining a loan to take. Some banks suggest this may still be a somewhat optimistic view,” he says.

4. Expense management. Surgery centers tend to have a level of fixed costs that generally require at least $3-$5 million in revenue to be significantly profitable and to cover the necessary expenses. Centers with $5-$10 million in annual revenues can, on average, expect to have an EBITDA of around 20 percent or earn about a 20 percent operating margin before deducting interest, taxes and depreciation. The three biggest costs for an ASC typically include staffing costs (about 25 percent of revenue), supply costs (about 20 percent of revenue) and general and administrative costs (about 14 percent of revenue). With staffing costs making up most of ASC’s expenses, it is critical to benchmark the hours per case to those at other similar centers in order to ensure that your staff is working efficiently. Generally, multi-specialty cases take between 13-15 hours and single-specialty cases take 6-8 hours. This number is often translated in simple terms to approximately five full-time equivalents per 1,000 patients. To control staffing costs, staff must be used efficiently by cross-training where appropriate, by staying open only as many hours as cases require and, if possible, by sending staff home when they are not needed.

Supply costs may be reduced by the use of a group purchasing organization or a hospital or management company partner that is able to aggregate expenses over a number of facilities and, as a result, benefit from volume pricing with vendors. Another common way to reduce supply costs is to standardize certain common surgical supplies and reduce the use of nonessential supplies. A seasoned management company can help a surgery center to achieve greater operational efficiency in both of these areas. Although staffing and supply costs can be modified over time, facility costs are much more difficult to change once a lease has been signed or construction has begun. It is very important to obtain expert advice relative to these three cost items early and often.

Equity ownership, physician partner issues and hospitals and management companies as partners

1. Management and equity ownership. It is important to determine whether or not your ASC will have a management company as an equity partner. An experienced manager can help with myriad aspects of the project, such as financing, financial planning and analysis, Medicare certification, equipment planning, construction planning and physician recruitment. A good management company can significantly reduce the likelihood of problems in completing the project, operating the center, financing the project.

Working with an experienced partner can help add focus to the project and help in areas such as efficiency and cost management. “Management teams allow physicians to focus on their core business, patient care and surgery,” says Larry Taylor, president and CEO of Practice Partners in Healthcare. “Since management companies take a lead role in the process, having their success linked directly to the success of the facility often leads to a minority ownership. By having the management company tied to the success of the center, incentives are aligned with the partnerships. Experienced firms sequence processes and the ramping of employees to reduce cost.”

Mr. Taylor says that the management team should produce results that are valuable to the partnership in both the financial and clinical areas.

“If a management company is an owner in an ASC, the financial performance of the ASC has a more significant impact on the management company than the size of their fee,” says Christian Ellison, vice president of Health Inventures. “Requiring a management company to put their capital at risk alongside the other investors appropriately aligns incentives among all of the stakeholders that drive value in the ASC business.”

The key downside to having a management company as a long-term equity partner relates to the disparate quality of companies that provide services to ASCs and the profits that are shared in bringing in a management company. Physician ownership alone can be very attractive under the right circumstances. However, an experienced management team substantially lowers the risks and, in most situations, can provide substantial benefits and improve profitability. Further, an equity owner/advisor often will have a much greater level of concern regarding the project’s success, even when it owns only 15-30 percent of the center.

The 2008 ASC Report from the Deutsch Bank says that the 25 largest management companies own interests in aggregate in about 1,000 of the country’s 4,700 Medicare-certified ASCs.

Critical items to negotiate with the management company include the percent of ownership, management fee, services provided, personnel employed or provided, length of the management contract, board rights and reserve or veto rights of the management company. A group should interview 3-5 management companies and talk extensively to other centers managed by the company.

In addition to a management fee, the leading management companies are increasingly requiring equity in the surgery center. Before rejecting such an arrangement, evaluate how that management company compares with other management companies. Mr. Ellison says that hospitals and physicians are increasingly requiring that management companies make an equity investment in the ASC to ensure that there is increased focus on the value creation that the risk creates.

A solid management company partner can also substantially improve the financing prospects of a center. Some finance companies will not finance an entity without an experienced management company being involved.

2. An ASC can have too many physician investors. Determining the right number of physician investors requires significant forethought and planning. With too many physician investors, there is often a dilution of individual physician responsibility and ownership interests. However, with too little ownership, physician investors often lose their commitment to the ASC and look for alternatives. Further, a great deal of resentment can develop between productive and less productive parties. Of course, with too few physician investors, the price of buying-in will be greater, there will be more risk of case volume losses with a smaller number of investors and the overall case volume of the center can suffer. The average number of physician owners in an ASC is approximately 15.1, according to the Deutsche Bank 2008 ASC report.

3. Single- or multi-specialty center. Single-specialty centers can be more efficiently staffed and built than multi-specialty centers. Moreover, a single-specialty center avoids competition relating to sharing space, profits and revenues with other specialties that is often present in multi-specialty centers.

However, changes in reimbursement can affect single-specialty centers more dramatically than multi-specialty centers. For example, Medicare has instituted significant cuts in ASC reimbursement for gastroenterology, pain management and, to an extent, ophthalmologic procedures. These cuts can disproportionately impact a single- specialty GI or pain management ASC’s overall revenue and financial health.

On the other hand, a multi-specialty center can help reduce reimbursement reduction risk through a diversification of reimbursement sources and a mix of physicians. In addition, a multispecialty center can provide for greater staff and physical plant economics of scale, which may be needed if single-specialty volumes are insufficient. In many cases, the operating margins in single-specialty ASCs are much higher than multi-specialty ASCs.

Barry Tanner, president and CEO of Physicians Endoscopy, says there are several things to think about when considering a single-specialty center as compared with a multi-specialty center.

“With single-specialty ASCs, no one specialty is subsidizing the costs associated with performing another specialty,” he says. “In other words if GI physicians working in a multi-specialty ASC are highly efficient and productive in terms of patient volume, they may perceive, rightly so, that they are subsidizing the higher costs (such as inventory, equipment, etc.) associated with performing orthopedic procedures.”

Mr. Tanner also says that there are the advantages to a single-specialty ASC. “We like to believe that because we do one thing, we do it very well,” he says. “When a patient goes to a single-specialty ASC, we know who you are and why you are there. This can improve both the patient experience as well as the overall quality of care.”

Mike Lipomi, president of RMC Medstone, says there are several important factors to consider between operating a single- versus multi-specialty ASC. “As a single-specialty facility, your ability to syndicate to additional physicians will be restricted to the practicing physicians in that specialty,” he says. “You will limit your ability to spread the overhead costs between specialties and to fully utilize the resources available in your facility.”

Mr. Lipomi also notes the areas of crossover in surgery centers, regardless of whether they are single- or multi-specialty. “Areas of the business office like reception, billing, collections and management can perform the same or similar functions for one specialty as well as multiple specialties,” he says. “The issue of rate fluctuations in a single-specialty center is a major concern. In a multi-specialty center, reducing reimbursement for one specialty is absorbed by other specialty reimbursement. This is better for the center as a whole and at the same time hurts those physicians who are getting better reimbursement.”

Specialty net revenues per case, according to the VMG Health 2008 Intellimarker, for several specialties are as follows:

The number can be heavily influenced by sample size and several factors such as out-of-network considerations.

Note: Look for part two of “Establishing an Ambulatory Surgery Center — A Primer From A to Z” in the May/June issue of Becker’s ASC Review and online at www.BeckersASC.com.

Contact Scott Becker at sbecker@mcguirewoods.com; contact Bart Walker at bwalker@mcguirewoods.com; contact Renée Tomcanin at renee@beckersasc.com.